I was an Arab-Muslim-Palestinian-Christian-American kid growing up in a quiet, all-white, insulated suburb of Philadelphia. I always knew I was a little different. I had parents and grandparents with weird accents. On weekends, my parents packed us in the car to go see other kids who had parents and grandparents with weird accents. I constantly heard stories of immigration, discrimination, and “otherness” from my parents and elders.

Even in my childhood (not that long ago), Arabs and Muslims were vilified in the media and entertainment. American Sniper, Chapel Hill, and Donald Trump are today’s reiterations of a long-standing atmosphere of Islamophobia and anti-Arab bigotry. Whether it was Iranian students, Palestinian guerrillas, or Libyans shooting at Marty and Doc, being an Arab or Muslim kid in the 80’s wasn’t that fun either.

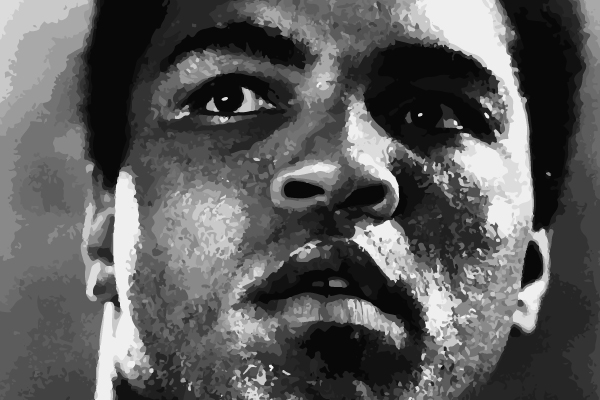

My grandfather’s name was Muhammad. He was also a survivor of the Palestinian “nakba” (“catastrophe”) of 1948, where Palestinians were dispossessed and exiled from their homelands. He eventually ended up in California, where he passed away in 2003. There’s a bunch of ways to spell that name, by the way. We really have to get our act together on that one. I actually remember that when I got old enough to notice it, I was excited that my grandfather spelled it the same way the champ did.

I got teased all the time as a kid.

“Do you guys eat camel?”

“Of course not,” I screamed back. I confirmed with my mom just in case.

“Watch out for the terrorist.”

“I live down the street,” I responded. I thought they said “tourist.”

“You have a weird name.”

“Oh yeah?! Well, my grandfather’s name is Muhammad. Like Muhammad Ali.” That shut them up.

We all know that Ali sacrificed his material professional achievements by refusing to fight in the Vietnam War. To be clear, however, he wasn’t a draft-dodger. He didn’t look for some technicality to get out of it (which he surely could have secured). He didn’t fake an injury or run to Canada. He stood in the face of his government and told it, unabashedly, “No.” Muhammad Ali taught us, very clearly, that sometimes in life, perhaps often, if you wish to truly be great, you must become an enemy of the state.

In American sports, we frequently use the term “world.” When a baseball team from Kansas City beats another baseball team from New York, we call them “World Series winners.” When a football team from Denver beats another football team from Charlotte, we label them “champions of the world.” But Muhammad Ali really was the “World Heavyweight Champion.” He can be the topic of conversation in any cafe in any corner of any city in the world. No matter where you were, his name is known.

So, sure, I could talk about Ali’s compassion, kindness, and influence. But to me, his defiance is what I remember. It’s what I identify with. America is a place that allows us to speak loudly, achieve proudly, and preach avowedly. But it also a place that oftentimes can alienate those of us who sound, look, eat, and celebrate outside of the norm. But Muhammad Ali made it ok for a young Arab kid in America to brashly, chest out, full of pride, inform everyone that his grandfather’s name was Muhammad too. Thanks champ.

Your grandfather Muhammad Jardali was also a great mman! Him and your grandmother, Layla Hawari Jardali, were my parent’s best friends in Akka.

You can be very proud of your grandparents who helped me get a student visa to Merced College in 1969. Upon arrival to the US, it was your grandmother who picked me up from the airport, and took me into their modest home for two weeks.

Your grandfather got me my first job pruning almond trees in the orchards that he managed. He taught me how to prune and wanted me to save some money before the start of the semester. Your grandmother used to bring me lunch and give me a ride back to their house at the end of the day.

When I remember the good people in my life, your grandparents are always the first that come to mind.

May your grandfather Muhammad rest in peace, and may God grant your grandmother Layla the strength and good health and the continued love of her daughters and their children and grandchildren.

Delightful article, Amer. Shukran.

I’m a Christian-Palestinian-Arab-American too (We’re friends in RL, Amer ;)

Anyway, kids in school used to make fun of me too because I’d sit down at the table in the cafeteria and pull out my Za3tar sandwich and eat it like it was totally normal while other kids were eating hotdogs, burgers, ham sandwiches….They couldn’t understand WTF was that weird green powdery stuff inside my weird bread that wasn’t sliced toast. I had no explanation. ‘C’mon, guys. It’s Za3tar! You don’t know what Zeit & Za3tar is??” Lol. I was accused of eating dirt sandwiches, eating animal excrement sandwiches, eating marijuana sandwiches. Finally I had had enough and went home one day and asked my immigrant poor-English speaking mom what Za3tar is in English. She didn’t know. It’s just….Za3tar. So I had to come up with a solution myself and that was….that I went to school and told everyone that Za3tar is dried up ground Seaweed and from then on, I was the kid that ate Seaweed sandwiches. Later on in life as I got more into the Culinary Arts (what’s up, Fatafeat!!), I learned that Za3tar was an herb called….THYME…pronounced “time” and that white people use it all the time too!! I could have avoided all those years of being the weird Arab kid by just telling my classmates that I was pita bread with a gourmet blend of Thyme and Olive Oil….or maybe not.